WAYWARD HEART

Chronicle of a cardiac arrest

by Pedro Serrano

Translated from the Portuguese

by Karen Bennett and Alex B. Carvalho

2015

___________________________________________________________________

First edition (Portuguese): Coração Independente, Relógio d’Água editors,

Lisboa, 2000.

Translation: Karen Bennett & Alex B. Carvalho

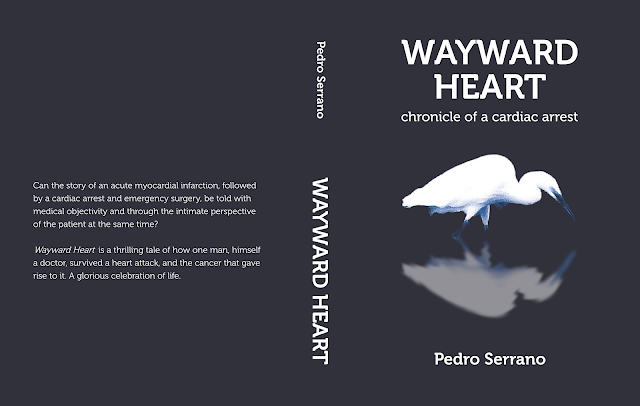

Cover: © Denise Ferreira over photography by Pedro Serrano, Ria de Aveiro, 2015.

© Copyright of this edition: Pedro Serrano, 2016-2022.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

To Manel and Gabriela, Isabel Costa, Ana Santos Silva, Vera Bonfocchi, and Carlos Orta Gomes

To the memory of Manuela Campos Monteiro, Mário Braga, Judite M. Neves, Nazaré Ferreira, Herman Anker, José Leitão, and Dennis Potter

Contents

Part I – Forever hangs always by a thread

Part II – It’ll be nothing serious!

Part III – Out of hours

Part IV – In the land of green broth

Part V – Beyond the traffic lights

Acknowledgments

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

What a strange way of living

Has this wayward heart of mine,

It lives a wild and loose life,

Who would give it the magic touch?

What a strange way of living.

O wayward heart,

Heart I can’t control,

Living lost, all apart,

Obstinately bleeding,

O wayward heart,

I can’t keep up with you no more,

Stop, stop beating now

If you don’t know where you go,

Why insist on running,

I can’t keep up with you no more.

From Amália Rodrigues/Alfredo Marceneiro

“Estranha Forma de Vida” (“Strange Way of Living” – fado lyric)

Part I

Forever hangs always by a thread*

* “Para sempre é sempre por um triz”. From the song Beatriz by Chico Buarque and Edu Lobo (O Grande Circo Místico, 1983).

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1

Sometimes, when I was small, and struggling to eat my soup, I would surreptitiously slide the blade of my dessert knife over another with a sly wink at one of my sisters or cousins. That was enough to provoke a delicious intermezzo. Inevitably, to our glee, our mother would bark out:

“Uncross those knives right away! You know I don’t like to see crossed knives.”

“Why, Mum? What’s wrong with it?” we would implore, winding her up.

Crossed knives presaged war within the family, just as surely as jumping over a prostrate body and failing to repeat the movement in the opposite direction would stunt that person’s growth. Laying a hat on a bed; opening an umbrella inside the house... my mother had a prophecy for each event, and there was a portent – good or bad (though most often the latter) – attached to every procedure.

Within her complex system of interpretations, there was a special chapter devoted to birds. Almost all of them augured doom – the sad hoot of the owl, the flurry of a sparrow accidentally imprisoned inside the house, the innocent flight of birds over our heads, even birds that had the mishap to fall into our path. None of this boded well for whoever had the misfortune to be nearby.

“Old wives’ tales!” my father would declare mischievously, pragmatically solid in his worldview.

As for me, I had never considered myself particularly superstitious – or at least, not to the extent of going around permanently downcast or anxious because of some forthcoming disaster. On the contrary, if I had assimilated anything of the lugubrious soothsayer’s faith that I had imbibed at home, it was tempered by the much sunnier philosophy of my father. Thus, if a pair of birds passed overhead as they winged their way southward, northward or westward, I would think of it as a good omen.

But there must have been some residual atavism lurking in my unconscious on the morning of 1st January 1999, when I opened my door and spied the tiny corpse of a newly-dead bird on the doorstep. For I was unable to rid myself of a thought that welled up from the remotest depths of my mind:

“Which of them will die first?”

“They” were my mother and Judite, the wife of a good friend of mine from Viseu. Both were suffering from the same type of cancer, and both had had operations that had apparently been successful. Indeed, for several years everything seemed to be going well and the absence of news suggested they were cured. Then suddenly, on one of those days that are never forgotten, there was a slight pain, a sudden tiredness in the street… And the nightmare had returned. We were on the road to Calvary, as the last stations of the cross showed up in the pitiless clouds of black and white on the X-rays and CAT scans.

And yet life went on, serenely for the most part.

As for the dead bird, the more objective part of my mind concluded that this was probably the work of our cat, Tangerine, who had the habit of dragging all kinds of unexpected presents into the house: birds, lizards, grasshoppers and other trophies. And the little bird lay there, stranded on the edge of the doormat, with one wing folded awkwardly like a disjointed fan, a handful of sad feathers scattered over the tiling.

My mother went first, in the early days of March, while winter was preparing to hand over the reins to spring, and the first green buds were starting to appear on the hydrangeas at my parents’ home. As for Judite, she left us six months later, at the beginning of October. Autumn had already arrived, and in Viseu, a sharp wind was pruning the leaves on the avenue of lindens, shrivelling the souls of the mourners returning from the cemetery.

But it is a risky business, trying to divine the future, as the old stories and fables repeatedly tell us. The sorcerer’s apprentice usually ends up in trouble if he dares to peer into the entrails, trespassing upon a territory reserved for the gods. I was no exception. Someone somewhere certainly charged the future with the task of showing me just how naive I had been in my interpretation of the portents on the first morning in 1999.

For I could never have guessed – nor even dreamed – that half-way through that scrap of time between the death of my mother and that of my friend Judite, there would be enough space left for my own death, which would occur (had I properly understood what that bird had had to reveal) in the last week of spring, at an as-yet-undecided hour.

2

I live near the sea, on a quiet street, a dozen or so kilometres from Cape Carvoeiro – that magic line which, according to the weather reports of yore, divides Portugal in half, bringing rain to the northern part while bathing the southern part in glorious sunshine.

But that was back in the good old days, before the storks dared come up to Alcácer do Sal to nest on the pylons that flank the River Mondego, when time seemed eternal and you could trust the constancy of the seasons. Not long ago, I was chatting about this with Nurse Edmea, whom I met coming up the side street from the Misericórdia, as I was on my way home for lunch. It had already rained three times that week, twice torrentially, and yet we were almost at the end of May, usually such a sweet month in southern climes! Clearly the climate was changing. Despite soothing assurances from the meteorologists that the monthly averages were “similar to equivalent periods in previous years”, no one was convinced.

I myself was prepared to be satisfied with the ozone-hole theory and the imbalances that it must necessarily provoke in the climate. But Nurse Edmea had another explanation! To my surprise, she was convinced that it was all caused by the satellites, rockets and other such artefacts that man had sent up into space, saturating the atmosphere! Perhaps Nurse Edmea’s theory was slightly unseasoned, but what did that matter if the problem was exactly that! What was this weather in May if not unseasonable? And the heat we’d had this year in February and March? Summer weather!

“My son’s been in the sea regularly!” I said, sharing my surprise with her.

June brought long days, but got off to an uncharacteristic start, sometimes grey, at other times luminous. It seemed undecided, neither fish nor fowl, not cold nor hot. And there was I, lolling in this marinade, on 17th June, a normal working Thursday, which slid past unremarkably with the same routine as all the previous days. At the end of the afternoon I returned home and worked a bit more before dinner. I was presiding over a recruitment committee at the time, and so my room was cluttered up with CVs – twenty-five in all – voluminous enough to tempt a mountaineer. I had stored them there partly through lack of space, though mostly so as I wouldn’t forget the task that awaited me. I sighed and, pencil poised, attacked the third of five volumes that constituted the curriculum vitae of the eleventh candidate.

Near dinnertime, we received a visit from a friend and her son, and they stayed for a while, exchanging tittle-tattle in the way friends do on mild afternoons. After they had been twice asked to stay for dinner, they suddenly noticed the time and left in a hurry. We three were already seated at table.

I ate little, feeling distracted and not very hungry, and gave up on the meal before my wife and son. I sat there, waiting for them to finish their desserts, nibbling occasionally at their conversation.

Slowly and steadily, I was being taken over by a strange sensation. I felt far removed from everything happening around me, an impression that my consciousness perceived with great surprise. I could hear them talking, but it was as if I were tuning in from another dimension, as if I had stalled in a state of indifference that had been imposed from somewhere deep within myself, from inside out. I didn’t participate in what was happening – I was inattentive, not because I was fixated on anything of my own, but because my senses had slid to another level. The usual stimuli did not seem to function; my gaze drifted out of focus and moved away from what it was supposed to be observing: I felt that I was seeing through, beyond... The remains on my dinner plate, a still life… In that state, I looked on as dinner ended and the people began to move, lifting glasses and cutlery and taking them into the kitchen. There was a low-level hubbub, punctuated by the enthusiastic vocalizations of my ten-year-old son. I remained seated, paralysed like a foreigner in that strange detached mist, so out of touch that even the sounds stopped making sense, becoming gaps, as if I had stuffed cotton wool into my eardrums, a high-pitched whistle like the valve of a pressure cooker vibrating deep down in my auditory canal. I put my fingers in my ears to try to dispel the acoustic confusion, shaking my head about to see if I could get rid of the feeling. Then, without warning, a wave of nausea came over me, and I stood bolt upright from the table, without pushing the chair out behind me. Goodness! How unwell I was feeling! I walked into the corridor, without any precise objective, only because my body urged me to move. I don’t know if it was the effort that did it, but, after just a few steps, I found myself suddenly soaked in sweat, a warm perspiration that poured from my skin like water from an underground spring, ridiculously abundant and swift: first the palms of my hands became slippery; then the back of my T-shirt was soaked through as if it had fallen into a puddle of water; after that, my chest, forehead, it was unstoppable… “What is this?” I wondered, from very far off, in the isolated depths of myself. I had reached the end of the hall and sat down on the bottom step of the staircase that led up to the next floor. The telephone was next to me on its little table. I sat. Then I realised that a new sensation was taking over as my body slipped even further out of my control. A tightness was grasping hold of my left arm as if the tendons that allowed it to move were being illogically stimulated, and there was a stiffening in my neck, irradiating upwards towards my lower jaw. That could only mean the heart! And whatever it was, it was most certainly serious….

Leaden, I looked around slowly, waiting for someone to notice me. It seemed as if the colours were all blurring into a shadowy grey, that the light bulbs were no long able to illuminate the night as they used to. Finally, my wife’s eyes met mine. I waited, knowing that she would recognise the absence imprisoned in my gaze.

“Pedro, what’s wrong?”

“I’m not well. Take me to the health centre.”

And I slid down the stair onto the floor, landing with a bump like a mass of boneless flesh, unaware even that Zé João, my little son, was watching everything.

3

I have all this on a reliable source – a bill from Portugal Telecom which I came across one day in a drawer, offering a “complete detailed breakdown” of all the calls made that evening. Thus it was that the stark facts of the matter presented themselves to me. In horror, I learned that at exactly 21 hours, 51 minutes and 53 seconds a call was made to the house of Vera, the friend that had visited us an hour earlier just before dinner, and that it lasted less than thirty seconds. “Come quickly, please; Pedro’s feeling really ill”.

Vera is a doctor at the local health centre, as well as a close family friend that comes round almost every day. The two families get together frequently to share joys and tribulations or just for the pleasure of the company. On this occasion, however, she recognised the tone of the appeal. Without waiting to find out more, she hung up and hurried out.

In the meantime, my wife had searched out the blood pressure monitor and was trying to measure my blood pressure and take my pulse.

“What´s up?” I muttered weakly from the depths of my torpor.

“The machine must be broken,” she muttered in exasperation. “I can’t hear a thing!”

I didn’t pay attention to the details. My body, and what was going on with it, did not concern me. I was a shapeless mass sprawled out on the floor, and my consciousness, reduced to the common lowest denominator, flickered like the flame of a candle.

I came round a little when we were outside the house. Revived by the cool night air, I realised that I was being transported on someone’s back, a dead weight with my arms and legs dangling inertly. I breathed in deeply… then came a view of a car roof and windows beaded with dew (something that happens at the coast, even in summer, because of the humidity – after an hour or so, a stationary car is covered with water droplets). My wife opened the car door as best as she could and pushed me into the back seat.

Vera arrived, got in beside me and rested my head on her shoulder. Then she opened the car window, which was a very good idea. My wife started the engine.

My son is with us in the car. No one has stayed at home. I can hear Vera’s rapid breathing near me and feel the fresh night air coming into the car. It feels good.

“Pedro, can you hear me? Does it hurt anywhere?” she asks in her Brazilian accent, as if from far away. “Have you got a pain in your chest?”

I try to shake my head, but have no idea if I manage to. (No, no, there’s no pain.)

Outside. It is dark and they are putting me into a wheelchair. Next to me is an ambulance with throbbing engine and nearby, a fuzzy patch of lights. I realise that I am at the door of the emergency department at Lourinhã Health Centre, though I’m not sure if that is because I can actually see it or because the place is so familiar to me. I am a doctor and have worked here every day for the last fifteen years. I know the building like the palm of my hand.

“I can’t see anything. I can’t see you,” I say to the air or to whoever is pushing my wheelchair. No one answers.

Inside, noise, confusion, shadows. I recognise the voice that addresses me – it is one of the receptionists from the health centre:

“Are you not feeling well, Dr?”

“I can’t see you,” I say. “I know your voice, but I can’t see you”.

I say the same thing to the colleague that receives me. The information might be important.

“I can’t see you – only a halo of light where you should be.”

I don’t say I’m blind, because I don’t feel as if I am. I just can’t see the people, though I can make out their bodies. They appear as luminous outlines of bright yellow light from which emanate familiar voices, as if through loudspeakers. I am calm, quite the reverse of panic. I don’t feel worried by the situation and explain over and over again, “No, nothing hurts. But I can’t focus on you. All I can see is a halo of light.”

Then comes a jab in the arm (they are pumping saline solution through my veins to irrigate them), a calm voice with an African accent saying goodbye (it is Clemente the nurse), movement, the crunching of wheels over a stony surface, the metallic clang of doors shutting… I am inside an ambulance and various voices are talking around me.

Someone places an oxygen mask over my nose and mouth, and I hear Vera’s voice murmuring, “I’m going to put a tablet under your tongue. Let it dissolve slowly.”

I open my mouth beneath the plastic. Everything is lurching and shaking around me – we must be travelling at breakneck speed. It is not at all comfortable, and the noise of clanking metal is deafening. I hear voices behind me, some apparently human, others more like the voices on a taxi radio. The pill tastes minty. The mask hurts my nose. I open my eyes and try to speak…

We go, we should go to Torres Vedras. My eyes are open, but I still can’t see. I am worried about the effect that this will have on anyone that looks at me – my dull expressionless gaze, unfocused and crooked. It’s annoying… Who is looking after Zé João? My eyes are open but I can’t see anyone. I can only see what is on the inside – lights, white light, no… yellow. I close my eyes and find it’s the same – an arch of light. I open my eyes and say…

I feel numb and limp, as if I’ve been slipping gently into sleep. I am not sure about the consistency, or even existence, of my body – or rather, I think I can see it lying there on a stretcher, on a level a little below where I myself am, as if I am moving away from it backwards, coming out of myself from the head end. My body lies there below, quietly waiting. Around this loose detached self a kind of circular tunnel is forming, with continuous walls made of light. It is an intense light, strong yellow in colour, a greasy yellow like the fat that floats on the top of a chicken broth.

“So this is the tunnel of light!” I think. “I’m on my way out”. I am surprised at how calm I am. If I’m dying, which seems to be the case, I am experiencing the moment with great tranquillity, no fear or anguish. Being. I am and I observe. There is not much to see. There are the shining walls of yellow light, though I’m not sure if the tunnel is completely surrounding me, if my self is completely contained within it. I am moving slowly, backwards, it seems, though I don’t seem to be changing place or level.

Suddenly I shudder and jerk, as happens sometimes on the threshold between sleep and wakefulness, and I find I am on the stretcher in the ambulance. I sense anxious breathing to my left. And I see – now I can see clearly – João and a young man in fireman’s uniform near my feet.

The mask is compressing my nose. I open my eyes and say, “This shit is hurting me. It’s horrible having to breathe like this!” To my left someone speaks. I turn my face slowly in that direction. I see Vera smiling. “Now you seem more yourself. Are you feeling well?”

I breathe in deeply, as if to check that I’m still whole. Above my head, the flask of the intravenous solution dances frenetically. Yes, I feel fine, in spite of the annoying mask. The oxygen is making my breathing light. It feels good. I hear a voice behind me:

“Five minutes, doctor Vera.”

“Warn them again that we are arriving,” Vera instructs.

The ambulance stops. Doors open with a bang and the fireman unhooks the flask from its support on the ambulance ceiling. The stretcher is moving. I recognise where we are - Torres Vedras Hospital at the entrance to the emergency department. I manage to say to my wife:

“João, if I have to go to Lisbon, try to get me sent to the Civil Hospitals.”

The trolley forges its way through to the inner door of the emergency department, and I pass through a column of heads, all craning to see if the package that has just arrived is in a better or worse condition than the one that arrived five minutes before. The usual menagerie of gapers, roadside voyeurs! I’ll be damned if they’re going to get any joy out of me!

4

The doctor wears glasses He unrolls a strip of ECG and scrutinizes it carefully. He shakes his head and says:

“There doesn’t appear to be anything here... Let’s get his top off so we can see better.”

He moves his hand towards his stethoscope, which nestles into his neck like a rubber and metal stole. I try to be cooperative. Supporting my body on my elbows, I raise my hands to my waist and pull upwards as hard as I can to release the bottom of my black T-shirt that is stuck in my jeans. Suddenly, everything ceases to exist.

5

It was Vera that saw all this. She was at my side in the Emergency room throughout the whole thing, and when she visited me, two days later, she told me what had happened. She has no idea how much it affected me, hearing her account. But I had to find out sooner or later. I was gradually becoming aware of the gravity of the event from the small details, the strange things that came to my attention in the following hours – though they were fragments, loose pieces of a jigsaw puzzle that I was unable to put together on my own. For of course I wasn’t there!

The moment I tried to take off my T-shirt, my body began to arch. My thorax thrust upward and a deep hollow appeared in my abdomen as if I had no entrails and the skin of my belly had suddenly got stuck to my back. I grimaced like one possessed; my eyes swivelled in their sockets and my whole body was racked with violent convulsions. Then came the impolite noises that health professionals primly refer to as “the loss of sphincter control”. Immediately after this, my lungs and heart stopped working. Full stop. I was dead. I was not yet irreparably dead, but I was undoubtedly more dead than alive.

Quickly – because a brain starved of blood and oxygen will hurtle rapidly towards brain death, which is definitive and irreversible – they did what they usually do in such situations, which is just like we see in the films. First they thumped me in the ribs over the heart. But as this didn’t work and everything in me remained stubbornly immobile, they had to resort to a defibrillator – that is to say, to electric shock resuscitation.

“We had to give you a little push...,” the doctor explained later with endearing modesty. “Your heart was being a bit lazy.”

“What do you mean ‘lazy’?” I asked, still befuddled, not understanding what he was talking about.

“Come on, try and get some sleep,” he interrupted. “You’ve had a difficult day. You need to rest. It’s important that you take it easy.”

Sleep?! How could I? It was impossible! For one, the morphine was keeping me awake, suspending me in a limbo that was tinged with slight euphoria, a golden fizz, gentle excitement. And then, of course, I also had a great deal to think about. I had to re-attach the thread to the reel, now that I had returned to the world of the living.

What could I remember? I had come round while I was still in the emergency room, though I was now on a moving trolley, heading to the ward. People dressed in white milled around me, though there was no one I knew. Suddenly, I had an incontrollable urge to vomit and my dinner came up, half onto the floor and half into the basin that had been hastily thrust under my mouth. Afterwards I felt better, because that dinner had in a way been cursed.

It is night and I am now lying in a bed, somewhere in the hospital, in a space separated from another bed (where someone moans softly) by an oilcloth curtain hanging from the ceiling. I can hear murmurs and, to my right, on the other side of a glass wall, figures pass by from time to time. My doctor suddenly pops up like a jack-in-the-box and peers at me. He doesn’t say anything but just stares, with an expression that looks apprehensive. I'm feeling all right – nothing hurts, and the bubbling of the oxygen and morphine lulls me. The events of the last few hours are parading across the blank screen of my mind, and although I am not quite sure how they link together, I feel intuitively that I have been party to some kind of miracle. My eyes fill with tears. There are a great many of them, a silent warm continuous stream. When they get too strong, I pull up the edge of the sheet to wipe them away and I see that I have my chest covered with electric wires, a metallic stubble-field. A male nurse checks the saline drip. He smiles at me and closes the curtain around me. Ensconced in my oilcloth cocoon, I eventually drift off to sleep.

Back in the emergency room, the cardiologist has a word with Vera, who has remained there to be updated on my condition, before reporting back to João in the waiting room:

“This is serious. Don’t raise his wife’s hopes too much.”

6

I am woken by the sound of castors clattering along the rail on the ceiling – the curtain that has sheathed me during the night is being pulled back against the wall. A friendly voice wishes me good morning and asks me how my night has been. Later, without lingering, it does exactly the same at the next bed, letting out another cheery “Good mor-ning".

I have a theory (though I cannot be sure that it has not been formulated before) that all people resemble animals when seen in a particular way or from a particular angle. It may be the shape of a face, an expression, a way of moving or even some psychological trait… what is clear is that there are creatures of all kinds – dogs, cats, lions, birds, giraffes (or, shortening the list into categories, mammals, reptiles, insects, birds, fish) – swarming about our pavements, restaurants and public transport in every city, town and village.

The nurse that moves about the room, going energetically from task to task, reminds me for all the world of a little sparrow – one of those that jumps around as if it were playing hopscotch with the lines of the paving stones, stopping here and there to peck at a crumb, or taking off from some high place in order to go and splash about enthusiastically in a puddle, emerging barely damp as if the water hadn’t touched it, only to fly off again to enjoy a gossip on a telephone wire. She is thin and frail, with the tremulous appearance of delicate animal, hair that is short and black as a crow’s wing, and large dark expressive eyes.

Like a bird, she also sings. She goes around the whole day warbling a tune (perhaps her favourite song, or something she happened to hear in the morning and couldn’t get out of her head), a song that I recognise perfectly. It is All I Have To Do Is Dream, by the Everly Brothers – a catchy song from the late ‘50s. As it happens, it is one of my son's favourites; when he was just seven, he asked me to record it for him, along with some others, on a cassette for his own exclusive use, and which he decided to call “Mixtureland”.

“Dream, dream-dream-dream,” she sings.

I learn from the ancillary worker that comes around behind her that the little sparrow is called Catarina and that the round metal bowls she clinks are for bathing the patients in the Special Care Unit, which is the name given to the room in which I find myself. One of those patients is me and the prospect of a bed-bath scares me. Taking advantage of a moment of privacy when I am handed the unequivocal glass bottle with the wide neck and the curtains close around me again, I lift the sheet and quickly inspect myself. To my surprise, I find I’m still wearing underpants!

However, I will certainly not keep them on much longer, as a matter of honour: last night’s loss of sphincter control (the implications of which I only realise now with profound mortification) makes imperative their immediate disappearance.

“They certainly gave you a good pummelling last night!” Catarina comments, as she rubs me serenely as if she is hand-washing a delicate fabric.

“Eh...?” I stammer foolishly, not understanding what she means.

Jutting out her chin gracefully, she indicates my chest:

“You're like Jesus! Just look at all the marks you’ve got, and a burn from the defibrillator.”

Lying down, I can only see three or four gauze suction devices stuck to the skin and a tangle of electric wires connected to them, with the transparent oxygen probe lying across them, so I try to sit up in bed.

“Keep still,” she says, smiling, but keeping me glued to the bed with a friendly but firm palm of her hand. “Wait for me to lift you. You mustn’t move so energetically just yet a while!”

My head is whirling with fragments of unconnected memories that do not seem to belong to me, as if they’d been put there by accident, perhaps having been accidentally switched with someone else’s. Vomiting, darkness, faces leaning over me, the clinking of metal, tears, jabs to the skin, a vague need to urinate, an unfamiliar pillow, cold bubbles endlessly fizzing, heat, dry skin and the desire to pull back the sheets; groans; a voice gently scolding, “Come on, try to sleep”…

These photograms, which light up insistently in front of my pupils are now starting to blend with a shapeless palpitating apprehension, which has not yet crystallized into panic because something in me is kicking the impressions and memories of the last twelve hours away into a deep abyss. I see myself, far away, slipping to the ground, my left arm imprisoned in the mesh of an invisible net; someone has put something minty under my tongue; “we had to give you a little push… your heart was being a bit lazy…”; underpants cruelly soiled; “just look at all the marks you’ve got... and a burn from the defibrillator...”

I wanted to ask what really happened to me, what truly took place, but I am fearful of the reply. I don’t want to know any more than I can handle.

In the end, it was sorted out without too much melodrama, as the evidence appeared where I least expected it, as so often happens in sad stories. In this case, the truth was revealed to me by a toothbrush! This instrument of revelation was brought to me by João during a bed wash in a bag of essential items: pyjamas, a pair of glasses, toiletries, comb, toothpaste, toothbrush...

As soon as Nurse Catarina had finished washing me, I grabbed the tube of toothpaste and the brush, and drawing back the sheet, made to get out of bed. There was a scream from the ancillary worker, and Catarina rushed to the bed, stalling me with a martial arts blow. I suddenly understood everything in its stark simplicity.

“Dr Pedro!” she said, with an expression that glinted somewhere between anger and amusement, “you must not get out of bed for anything, do you hear me? You want to brush your teeth? – you can do it in bed. You want to urinate? - you can do that without having to get up too.”

And, noticing my stunned look, she added:

“It is important that you don’t make the slightest effort in these early days. It’s vital for your heart that your body is completely at rest.”

My dismay was undisguisable. Trying to cheer me up with her smile, she whispered in her most chirpy voice:

“Fatinha and I will help you with anything you want or need. You only have to say… OK?”

And as she breathed out that “O”, her narrow lips formed a perfect circle of delicately lipsticked lines.

I nodded and murmured OK, silently aware of the gravity of my condition. Jesus! The banal gesture of getting out of bed had been neutralized as if I had been preparing to detonate an explosive device in the bathroom, placed somewhere in the washbasin, next to the paper towel dispenser. All right! I get it. I should have known.

So, my condition was so serious that the simple variation between lying down or standing up could make the difference between life – sweet life that I had known and wasted – and death – that of books, films, others.

There was no point in trying to hide things from myself any longer for information was coming at me from all sides. The clutch of news that João has brought from outside confirms my changed state, and the messages and greetings (“he mustn’t worry about work”, “what he needs now is rest; he has to think of himself”) show that people everywhere in my network of contacts are confused, worried, sympathetic. Some of them would be still half-stunned by the early morning phone call, wondering where on exactly Torres Vedras was, and realising with a shock that they had completely forgotten to ask João what department I was in.

7

The Special Care Unit at Torres Vedras Hospital is a spacious room in the heart of the Internal Medicine department with which it communicates by means of a door located to my right. It is physically separated from it by a glass wall, so anyone passing by can see us as if we were in a fish tank. We, meanwhile, floating about in our oxygen bubbles on the other side of the glass, can also see them approaching along the corridor.

The wall opposite gives onto the south side of the hospital, and through the large expanse of windows, I can see the tall undulating waistlines of poplars, swaying amidst a dusty line of cedars. In the distance, beyond the untidy buildings, as if drawn by a child, is a soft green mound, straddled by a little road.

The Special Care Unit has four beds, but at this moment, only two are occupied: mine (which is near the door, against the glass wall) and the one on my left, which contains an elderly lady, who is preparing to be transferred to Lisbon to have a pacemaker fitted.

However, Nurse Catarina thinks that the calm that reigns in the Unit is unlikely to last long, as downstairs Dr Brito is in charge of the Emergency Department. When he’s on duty, complicated cases inevitably appear requiring hospitalization in the Special Care Unit.

“As sure as fate...”

Fatinha nods her agreement.

And in fact, half way through the afternoon, when Catarina and Fatinha had gone off duty, the tranquillity of the Unit was shaken by the tempestuous entry of a trolley. On it was a contorted shape that was hastily transferred to the empty bed opposite the old lady's. It was a man, agitated as a fish that has just been tipped out onto the bottom of a boat, moaning aloud in pain and lifting his hands clumsily towards his chest. A myocardial infarction, that much was clear – though nothing like the one I had, which had been quick and painless like the perfect depilation. Dr Brito and the nurse bustled around the patient, but his pain-provoked anguish made him difficult to control. For another dreadful hour, the poor man convulsed, tearing at his chest with his nails, as if a serpent had driven its poisonous fangs into him. I watched in dumb horror, unable to do anything else.

Eventually (I was exhausted just watching him) he calmed down and fell into a heavy slumber. The staff were finally able to breathe a sigh of relief.

Now that he is asleep, with his face relaxed into that blessed-child expression so common in sleepers, he looks familiar. I scrutinise him, though it doesn’t help that he is lying down rather than standing up, bare-chested rather than clothed, immobile in sleep rather than awake… However, I could almost swear…He looks amazingly like Fidalgo, a civil engineer from Lisbon, who also works in Lourinhã, and is building a second home very close to mine. I bumped into him only yesterday in Dona Ção’s cafe, and he was exuding confidence, discussing the properties of pre-stressed concrete with João and another architect (in fact, I slipped away when I realised where the conversation was heading). Who would have guessed that here he would be today, fighting for his life! It is him, I’m sure it is.

Near dinnertime, while he was still sleeping, João arrived with some telegrams, fruit juice and news from our road.

“Guess what’s happened to Fidalgo?”

“I know,” I said, pointing to the bed opposite. “He’s had a myocardial infarction”.

João didn’t know why Fidalgo had been taken in, only what had happened up to his departure for Lourinhã Health Centre. She thought he’d have gone straight to Lisbon, or perhaps to Cascais Hospital, where his wife worked. Earlier in the day, the engineer had seemed pleased with his work, directing the builders, helping to carry materials that looked rather heavy. But some pages further on, he had begun to feel ill, very tired and sweaty, though he didn't pay much attention to it at first. He had rested a little, smoked a cigarette and gone back to work. Then he’d felt ill again, this time with an alarming shortage of breath and feeling as if a nutcracker was squeezing his chest. He couldn’t go on and was taken to the health centre, which immediately sent him on to Torres Vedras.

Dusk has fallen. The windows overlooking the street reflect the lights of our ward, and although you can still make out the faded texture of the red sky, it is now almost suffocated by the dark blue hues of night. Tomorrow will be another hot day.

The lamp behind my head (one of those with an adjustable neck) is shining on one of the books that João has brought me. But I can’t concentrate on reading. My attention is constantly distracted by some noise in the corridor, or by the sight of Fidalgo, who slumbers on gratifyingly, with one hand protectively clutching his chest.

“Sleep, sleep, Mr Fidalgo. Everyone that saw you arrive wishes you the long sleep of the just.”

The night nurse is an olive-skinned woman with soft skin and a thick mass of dark hair which frames her girlish face, setting off a delicate neck that curves graciously down to her shoulders. Hardly has she sat down at her worktable next to the windows than she lifts her hands to catch hold of her hair and twists it into a ponytail with an elastic band that she clutches between her teeth. It's a pity. This constriction of her tresses – though of course more appropriate for working and more hygienic for us: the poor patients – does not erase her charm altogether, but it makes her look more like a carousel pony than a siren. She is called Inês and she is interested in the books that João has brought me. She asks to have a look at them, and later wonders if I would let her have one to read during the quiet moments of her shift. She tells me that reading is her favourite pastime and that her favourite writer is one of the Brontë sisters – Charlotte, if I remember rightly.

As if we were in a pub that is getting ready to close, Nurse Inês gives us the first signal that it is time to sleep by turning off the music that plays quietly in the background. Here, however, the punters cannot leave by the door, grumbling, nor can they take advantage of the warning to lie down – for they are already lying down. All they can do is wait for her to put their beds down and for sleep to deign to honour them with her presence.

“Do you want me to draw the curtain?” she asks.

I don’t. With the curtain drawn, I feel like a parrot whose cage has been covered over to deceive it into thinking it is night. Despite the light, I prefer to be in contact with whatever is happening around me.

Time passes. I am not sleepy. I’m not used to that bed, nor to sleeping with so many people around me. With my eyes open, though taking care to be discreet, I watch the nurse, who has not stopped for a minute since she came on duty. There always seems to be one more task for her to do, though to my eyes they might just as well wait till morning. Looking serious and concentrated, she goes around meticulously tidying, arranging things. She gets up silently, checks some detail and then goes back to her small worktable to record it. She writes, writes, writes. Nurse Inês writes as if she were racing the clock to express her final wishes.

To my surprise, I feel my eyelids growing heavy. The whirr of the oxygen becomes fainter till it is no more than a soft hypnotic buzz. But I struggle not to fall asleep just yet – I am fascinated by Inês’ reading and I want to see the film through to the end.

Finally, she seems to consider her work finished. Now she gets up, presses lightly down upon the back of a black armchair that is waiting nearby and pulls back the arm of the lamp that has been illuminating the work table till it spills only tiny pool of light onto the top of the armchair. Finally, she leans back in her improvised couch and opens the book that I have lent her.

I cannot keep my eyes open any longer, and my mind is growing indifferent to the coordinates of my location. My uncertainty about what tomorrow will bring is gradually muffled by the outpouring of silence, softly threatened by the turning of a page.

— ˜

The trio of patients that Nurse Inês watched over during the night became a quartet on Saturday morning with the arrival of a new patient, who entered the scene even more dramatically than Fidalgo had. This one was not only contorted on top of the trolley – and moments later, without any apparent transition or pause, on the bed – he also cried aloud in pain, clutching at his chest and left arm. Another infarction? It seemed so, though this fellow (who I could see clearly because he was less than two metres away from me) could not be more than thirty years old! That was very young for an infarction, though Dr Brito had let it slip that “... it used to be very rare for us to get infarctions in people under fifty... Now they’re appearing at thirty, sometimes even younger!”

However, when he calms down, António Luís claims that his problem has nothing to do with his heart; he pricked himself on a cactus, he says, and it was this that caused the pain in his arm and chest.

The doctors didn’t believe his far-fetched explanation, and, airing hypotheses such as an infarction or pericarditis, decided to treat him as if it were in fact a heart attack. Although this was an eminently sensible decision, it exasperated him.

“Hey, Gorgeous,” he said to the nurse on duty, a redhead with hair in ringlets, “I can’t stick around here in bed! I’ve got to get up.”

And she had to call the support doctor to the Unit to impose respect, because, now that the pains had completely gone and he had started feeling the claustrophobia of hospitalization, nothing could convince him that he couldn’t go home right away as if nothing had happened.

The doctor scolded him severely and António Luís listened humbly with his head down, though he was looking at me sneakily with amusement shining out of his blue eyes. Then he winked, inaugurating our complicity.

We quickly became accomplices, António Luís and I, united by circumstance, by our faces in the mirror (if I sat on the bed it was his face that stared back at me) and by our aesthetic pleasure in the youth, beauty and variety of the feminine element that surrounded us and is taking care of us.

“Dr,” he hissed, nodding towards the corridor, “just look at that vision!”

Visions... We were indeed blessed to be surrounded by beautiful, interesting, captivating visions, who lit up our day as the stars light up the night.

But António Luís was not satisfied with mere contemplation and couldn’t resist addressing gallantries at every woman that came near, which he did with a roguish innocence.

“May I know your name?” he asked the dazzling beauty that came to take the electrocardiograms, stretching out his arm with the solemnity of one that is waiting to receive an engagement ring on his finger.

The girl refused to give her name but smiled in amusement. António Luís advanced another step:

“Do you, by any chance, live here in Torres Vedras?”

And as she shook her head in a slow negative without interrupting the process of placing electrodes on António Luís’ chest, he took another shot.

“That’s a pity...; because if you did, I would invite you to come out with me one of these days.”

Of course all this was blarney. António Luís didn’t live anywhere near Torres Vedras but some twenty or so kilometres away with his wife and toddler.

My days brightened up considerably after his arrival in the Special Care Unit. I enjoyed his roguish patter and was amused by his theatricality, which oscillated between melodramatic complaints and ostentatious gallantry.

“My love,” he says to the ancillary worker that brought the dinner trays, “I really can’t eat this! – I think I’m going out to dine...” Availing himself of Smile No. 37, he added, “You could come with me. What time do you get off duty?”

I shared António Luís’ opinion of the dinner. The food here was terrible, a handicap that was only now beginning to dawn on me. In my first few days, they hadn’t give me anything more than a cup of tea, yoghurt, and an occasional baked apple, which had generally allowed me some latitude to eat. Then they added soup, which also went down without any gustatory surprises. But when I went back to a solid diet, I found that the food was terrible! Maybe I was being fussy! But a half-raw potato that looks from the outside like a boiled one does not, to my mind, fulfil its noble destiny of providing nourishment!

8

I don’t know where my watch is, but the sun has come up, and as yesterday was Saturday, I guess that it must be Sunday. Shortly after lunch, Zé Marques Neves passed by on his way from Viseu to Lisbon. Given my indisposition, he is going to replace me as president of the examining board in the selection procedure that we had been preparing since January. The first interviews were booked a month ago, by me, for tomorrow morning!

I saw his upper half advancing behind the glass wall that separates us from the corridor. His smile was restrained, as if he were making an effort not to stretch the corners of his mouth too much and reveal the emotion of seeing me like this. When he opened the door and came in, I noticed that he was wearing shorts! This was nothing like his usual formality.

“Zé, I don’t believe it. A doctor, an important guy like you, coming into a hospital in shorts!”

“What do you expect? It’s a furnace out there!”

There was no point telling Zé all the details about what had happened or even the more recent developments in my clinical condition – he already knew everything, right down to about an hour before. When we spoke about my illness, he carefully sieved his words, so that none of them could be taken hostage in my state of heightened sensitivity and used to darken my spirits. He moves on to less hazardous terrain.

“I’ve just been round to your house. I went to get the files for the interviews. My boot is full of boxes and papers.”

He didn’t linger. Announcing that he still had to go over the questions he meant to ask the first candidates, he made ready to leave. I detained him one last moment to ask after Judite, his wife of some twenty years, whose health had been in a precarious state lately.

“What about Judite? How is she?”

For a brief moment, his good humour, so valiantly maintained, dissolved. His mouth tightened and a look of anguish flashed across his face.

“Today is not a good day to talk about that…,” he said, saving me from discomfort with a sad smile.

I shut up and changed the subject, wanting to allow him some minutes’ respite from the martyrdom that he had left behind at home. Judite had had surgery for cancer some years before but had managed to remain disease-free for a comforting number of years. However, the illness had returned when it was least expected, disseminating malignant cells throughout her whole body. Despite the evidence, Zé was refusing to acknowledge the ruthless spread of the disease, which was crushing him like an insect each day that flowed by.

“Goodbye, lad,” he said. “Behave yourself.”

I watched him disappear into the corridor. After glancing quickly around at my slumbering companions, I dived under the sheet to hide my damp eyes. Holy shit! Just look at the state I’m in!

The hot weekend flowed by, slowly and lazily. There were flocks of visitors in the corridor, who would glance curiously at the specimens in the Special Care Unit as if we were snakes in a solarium. This was understandable. All four of us had heart monitors on our bedside tables, tubes attached to our noses, electric wires glued to our chests and flasks of saline solution dripping into us. We were personifications of that frightening and rather alien condition that is disease!

But what they don’t know is that I am feeling just fine lying here, and that the same can almost certainly be said about António Luís (when he is not making a scene to call attention to himself), the old lady on my left, and even Fidalgo, who is sleeping peacefully with his mouth hanging open. That would confuse the gapers on the other side of the glass.

My appearance may be rather off-putting, and my clinical condition is said to be serious, but if it were not for the prohibition on getting up, I would say that I was in perfect health. This is a rather confusing situation to be in. We feel just as we usually do, but they treat us as if we’re about to kick the bucket at any moment.

Judging by the heat and the rather spaced-out look on the faces of the people that came in from outside, this is clearly a perfect summer weekend. There isn’t much to do here besides skim one or two paragraphs of a book and listen languidly to the songs emanating from the small sound system lodged on one of the shelves beneath the windows. This is generally tuned to Radio Nostalgia – or at least, it is when Nurse Inês isn’t on duty.

“You can have too much nostalgia!” she complains disdainfully, changing the channel immediately.

Dissonances... Of the various people here, it is myself and Nurse Catarina (who is over thirty-five) that most appreciate Radio Nostalgia. We know all the songs – they are from our time and we can sing along, if only in our heads...

Let’s all get up and dance to a song

That was a hit before your Mother was born...*

But Nurse Inês is only in her early twenties and prefers more modern music, songs written in the days that run in her veins. These will be the very songs that she will be humming to herself a dozen years from now, if history runs its course. But that is in the inscrutable future. For now, the only thing that counts is that she is just not old enough to be nostalgic.

Dr Daniel Varanda, the doctor that got the booby prize of me and my cardiac arrest, is old enough to understand the concept of nostalgia and he reappeared, after the first weekend, to inform me that tomorrow...

“...we’re going to give you an echocardiogram to see how you are, and if everything’s stable, we’ll send you to Lisbon for a coronarography.”

“Coronarography?!” I repeat, apprehensively.

“Yes. We have to find out why this happened to you. You don’t think it would be a good thing?”

What I think is not really the point. I do think it would be a good thing, yes. But the idea of a coronarography! It is not very nice to know that they are planning to stick a probe into your artery and push it through to your heart, and that they will then inject you with a contrast solution which, like the flash of a camera, will illuminate all the twists and turns of your heart’s circulation system for posterity.

“And when’s that going to be?” I ask in a hollow voice. “Where are you going to send me?”

“Listen, mate, you seem to be in a bit of a hurry to leave us!” he said, putting on a harsh voice. “Let’s do this in stages. First we have to see how your ticker is behaving and then we’ll deal with the rest. If all goes well, we’d like to know what’s going on this week.”

Seeing my dejected expression, and not wanting to leave me without saying anything further, he asked:

“All right?”

It wasn’t OK – in fact, it was terrible – but I said it was. What can you say to the man who saved your life three days before, and, if that weren’t enough, is also as obstinate as a mule?

I sat there gloomily thinking about it, half following the animated conversation between a playful António Luís and a health ancillary who was making compresses from layers of white gauze.

There is a nurse and ancillary worker on duty at all times in the Special Care Unit, and this set-up causes some jealousy amongst the rest of the hospital staff. Maintaining such an army for only four patients is considered a luxury of oriental proportions, even though the whole purpose of the Unit is to keep a close eye on high-risk cases, as its name suggests.

Personally, I wish that we could see a bit more of that luxury on our meal trays, which unfortunately come from the common kitchen and continue to be entirely unpalatable. Only the treats that João brings me each visit – yoghurts, fresh fruit, biscuits, jam – make up for it. I have just finished dinner, pushing the leftovers as far away from me as I can, and am concentrating on trying to blur the cinnamon squares on the top of a rice pudding which a neighbour has smuggled in to me.

The Unit is quiet and calm, just like the night peeking in through the windows. But this is a calm laced with fatigue, thick as the August dust. The old woman in the next bed was sent this morning to Lisbon to have her pacemaker fitted, and Fidalgo, who is sleeping with his face turned towards the motionless poplars, will go tomorrow to a hospital in Lisbon, where he knows people.

“Looks like I’m going to be left alone,” complained António Luís, when I told him the news about my coronarography. “The old girl’s gone; tomorrow, it’ll be the engineer; then you...”

“Now don’t exaggerate!” I reply. “I still don’t know when I’m going, and if I do, I’ll go and come back in the same day – they don’t want me there going to seed!”

“Who knows?” he said, looking as despondent as if he would be the last man left on the planet within a moment or two.

“I do,” I said. “In two or three hours, I’ll be back here again.”

It was time for Nurse Inês’ night shift again. As we were now old acquaintances, she took the opportunity to glance through my growing pile of books and magazines when she came to lower my bed.

“Would you lend me this just for today?”

The radio was turned off, as were the lights, except for the lamp on the work desk. Nurse Inês left the Unit for a moment to go and eat something in the nurses’ canteen – it was time for the last supper.

I snuggle down, adjusting my pillow to make the perfect hollow for my head. From outside in the corridor I could hear the occasional murmur of faraway voices, the clinking of metal, the sound of a door squeaking on its hinges, the sound of something rolling along. Sleep...

Sleep is beyond the reach of the will. And it’s not something you can easily fool. Since I’ve been here, I have been divided each night between the desire to be gathered up by the wings of sleep and the stubborn need to remain awake, to surprise death, should he be prowling around here. I would play hard to get. I had no intention of going off into the dark night with him like some giddy young girl that is easily seduced. The deceitfulness of him, and, at the same time, the brutality, as he pulls the mat out from under your…

“Dr? Are you asleep?”

“No”, I reply, in an audible whisper.

“Good night,” says António Luís, half propped up in bed, his blue eyes shining in the gloom. “We can sleep peacefully tonight, can’t we? – we have an angel watching over us.”

“Yes, I suppose we have,” I agree. I return to my beaded thoughts in slightly better spirits. “Good night. Sleep tight.”

9

I had never spent my birthday in a hospital bed – in fact, I had never actually even been in hospital before. But there’s always a first time for everything. Today, a Tuesday, I am 46 years old, a number I only just made by a cat’s whisker. Suddenly I feel like saluting with an old cliché: “such a nice age!”

If it were not for the circumstances, I would be spending the day just like any other, listening to the same tedious old stuff on the telephone, shrugging disparagingly at any attempt to celebrate my birthday and mulling nostalgically over the passing of the years. But not his year!

I unwrap the presents that arrive, read the messages, and get a visit from my son Zé João (whom I haven’t seen since the day of the heart attack). Vera and her children come too. Then, towards the end of the afternoon, a young colleague appears clutching an enormous bouquet of flowers in one hand and balancing a green pot plant on the other. He is representing a dozen other colleagues, who in a greeting card covered with familiar signatures, urge me to get well soon and wish me “all the best” and “many more years of life”.

Now, engrossed in a dish of magnificent cherries that João has brought to liven up my dinner, I watch, with satisfaction, the effect that my bouquet of flowers is having on the people at the reception desk on the other side of the glass. It was Fatinha who searched out a vase, filled it with water and arranged the flowers. Before going off duty at eight o'clock, she opened the door of the Unit to say goodbye, hugging the pot plant that I had just given her.

“I’m going to look after this really well, so that, after you leave, I’ll know that you’re all right if it’s thriving...”

I stare at her stupidly, not knowing how to reply. It is António Luís that reacts, sticking his head out over the edge of the bed:

“Oh, Dr, that was really nice, that was...”

Some time after dinner, one of the ancillaries came to take me down to the catacombs on the ground floor where the testing rooms were located. As usual, I go wherever I am taken, always with zero effort, wheeled along on the trolley. This time it was to do the echocardiogram that they had warned me about, a test that uses the bat’s favourite navigational tool – ultrasound – to assess the functioning of the heart.

Sitting at the computer in a white overall is a thin dark man that I don’t remember having seen before. He is not very communicative and doesn’t say a word as he rolls the probe around in the slimy gel that he has spread over my thorax.

“You’ve had an extensive infarction,” he says, finally. “But you’re recovering well and the myocardium is revascularizing quickly.” As he bids me goodbye, he adds:

“Let’s see if we can get you to Lisbon this week to do the catheterization so that we can find out what this is all about.”

“Do you know what hospital they’re sending me to?”

“No, not yet. We’re dealing with that now. It’s usually Santa Maria or if not, Santa Marta.”

“If it’s at all possible,” I say timidly, “I’d prefer to go to the Civil Hospital, to Santa Marta.”

“I can’t promise anything. It doesn’t really depend on us; it depends on the bookings... Speak to Varanda about it.”

The following day, I accosted Dr Varanda as he came into the unit.

“Dr, where I am going to do the coronarography?”

“I’ve just been sorting that out, mate. The Santa Maria can only take you next week, so we’re going tomorrow to the Santa Marta, late morning. I’ve arranged everything with Gil Seabra, the colleague’s that’s going to examine you – he’s a good chap, very competent, you’ll see.”

I thought I could feel a gust of good luck beginning to waft around me. However, it soon dwindled and died out in the sequence of remarks that followed the doctor’s final observation:

“Nurse, don’t forget to prepare this patient for the catheterization.”

After he’d left the room, I wanted to know what the preparation involved, imagining, in my ignorance, special diets or fasting, medication; maybe even radical enemas...

“Oh, it’s nothing special,” she replied. “We only have to shave the hairs off your pubis and groin”.

10

It is St John’s day, 11 o´clock in the morning. And here am I, for a few brief moments – the time it takes to put my stretcher into the ambulance – out in the open air on a gloriously hot morning. St John’s day is a public holiday in my native city and also in my adoptive town. At this time, in Oporto, most people will still be snoring, and any early birds that are around will be lamenting the excesses of the night before as they nurse their hangovers. The refuse collectors will be out in the streets, cursing the mess left by the revellers. In Lourinhã, where tradition has never been taken too seriously, everyone will be on the beach in the heat – that’s the usual custom on St John’s morning.

Nurse Catarina is coming with me to Lisbon, a blessing which I receive as evidence of St John’s largesse. I couldn’t have chosen better company – her manner, tone and efficient kindness has a calming effect on me, bringing me peace.

The ambulance goes off down the motorway at a steady speed. There is almost no traffic on the road at this time and no one is in a hurry. This lets me keep an eye on the landscape and an ear directed at Catarina, who is telling me (with regard to how quick it is to get to Lisbon these days) about the painting lessons that she has there twice a week.

“So you paint?” I remark. “I had no idea!”

I glimpse passion in the captivated tone she uses to describe her pastime and the bright dreamy look that takes over her dark eyes.

We have just passed one of those giant Father Christmas hats that dangle in the middle of the central reservation to indicate the strength and direction of the wind.

“What time do you think we’ll get back to Torres?” I inquire. I am expecting a visit this afternoon from Ana and João Vasco, my niece and nephew from Oporto.

She doesn’t know. It is difficult to give precise times with the Lisbon hospitals – though if all goes well “perhaps around four or five o’clock”.

We pass pylons – haughty metal scarecrows with the stunted arms of thalidomide victims, holding up a heavy curved skein of thick electricity cables. These wires stretch and grow straight as we draw close to them, and some are threaded with coloured balls like the beginnings of a gigantic bead necklace.

Catarina is chattering away at my side. She tells me about the years she spent in Holland, her daughter, her family, her work at the hospital.

We are going down towards Lisbon. Behind us is the landscape of soft hills, which charmed me with its sweet undulations when I moved down here fifteen years ago from the majestic mountains and sharp outlines of the north. It was like entering a naïve painting.

Through the window nearest my head, enormous boards parade by before disappearing into the past. Some are blue, some white, and they mark the various routes that it is possible to take: the motorway to the South, Vasco da Gama Bridge, Odivelas, Lisbon… How strange it is to see the street (we are in the Calçada de Carriche) from this perspective, upside down. Buildings lean in on me on all sides, threatening to merge at the top like a Cubist take on of a country road lined with trees. Street lamps nod incessantly over me like giraffes; traffic lights with winking eyes; covered balconies, windows, and glazed buildings glinting as if they are covered in silvery blue fish scales.

The city is sluggish in the heat, and the traffic flows slowly. Suddenly, in the red of a traffic light, I recognise the rusty brown colour of the Picoas Forum. We are crossing the city heading East.

The ambulance slowly pulls into the garden of Santa Marta Hospital. I have been here before, but upright. I came here one afternoon, for a work meeting with colleagues – it was also summer, I recall – in the office of the director of the Cardiothoracic Surgery department. As usual, I paid little attention to my surroundings, though I vaguely recall an old garden and some building works, a shaky old lift, a room with extravagantly-framed photographs and diplomas on the walls, and a suffocating heat.

They park my trolley near a wall and we wait, Catarina, the fireman and I. Time passes. It is already past lunchtime, and as I have no choice but to fast, I insist that they go and get something to eat. There is no point in all three of us suffering. They resist for a while, but in the end, hunger gets the better of them.

When everyone has gone, I take a throat sweet from under the sheet and suck it, just to keep some sugar inside me. I know that the only reason they want me to fast is because of the vomits, not for any other reason, but I don’t want to spend the whole day feeling weak and faint, with my stomach rumbling and swelling like a hot-air balloon!

I am completely engrossed trying to lick the lustre off the sweet with my tongue and swallow the sweet saliva, when suddenly, without a warning, everything begins to shake. The trolley starts to move, and then a young man appears at my side. He greets me affably, telling me his name (startled I don’t understand him) and he starts talking to me in a slow shy voice. I realise that this is the doctor that is going to do the coronary exam. He looks slightly oriental. A grey-flecked quiff flops across his forehead, and it wouldn’t take much to make him into the stereotype of the mad scientist that we imagine from literature or see in a James Bond film, labouring away in a machine-filled laboratory for the good of us all.

“I have spoken to your doctor at Torres Vedras. I know all about your history...” he tells me quietly, making the link between my past and my present, anchoring me into this new reality. I feel that he doesn’t do this by chance. He looks attentive, like someone who understands just what gets lost in the corridors of illness, as if he has not forgotten that a patient still has, at the very least, a being with a head, body and limbs.

And he stays by my side, smiling rather crookedly with his slightly lopsided mouth while the trolley enters an enormous room without any visible windows. It is almost dark and filled with equipment from a science fiction film and people wearing green masks. Carefully, they transfer me onto a bed that is lit up like a stage. It looks for all the world like an operating table.

“Catarina won’t know what’s happened to me when she gets back from the bar,” I think.

The doctor briefly explains what he’s going to do and asks me to tell him any sensations or alterations that I notice during the test. Then I feel a small jab in my groin. They’re giving me a local anaesthetic. I see him pick up a long round white thing, rather like a curtain wire. I guess this is what is going to be inserted into my iliac artery and pushed upwards mole-like to my heart. I feel no pain, only a warm sensation in my thigh (probably some blood spilt as the catheter is inserted). Then a shudder, a yelp, as if some strange body had touched my heart, causing it to erupt into faster beating.

“Now you’re going to get a feeling of heat,” the doctor warns.

I have had that sensation before. It is the contrast solution spreading about my body, a burning as if they had tipped a double shot of whisky directly into my veins. I felt it travelling about my body at rollercoaster pace, marking out two places on the way – the roof of my mouth, which became as hot as if they had applied a mustard plaster to it, and – would you believe it? – the pubic area.

“Just once more,” says the doctor, working the probe.

Again comes the heat and a delicate pain. I complain, as we arranged.

“That’s it... I was just observing the internal mammary artery.”

“The internal mammary?” I wondered to myself, mentally revising the anatomy of the area. “So the exam was not only to check the state of the coronary arteries?”

With a snap, the doctor managed to take off his rubber gloves, which had stuck to the tips of his fingers with sucker-like determination. I heard him whisper off-side:

“Get me a bed.”

And then, with a hand on my shoulder, he said calmly:

“I’m afraid you’re going to have to stay here.... We’re going to have to operate.”

“Operate? On my heart?” I echo stupidly.

“Yes. We’re going to have to do a by-pass... This isn’t at all good. You’ve got 90 % obstruction of the common arterial trunk*.”

I don’t say anything. What was there to say? I am overwhelmed. This is a blow from the air, so strong it stuns. Noticing my catatonic expression, the doctor adds:

“Don’t get upset. It’ll be fine. The internal mammary artery is in good condition for grafting. Tomorrow or Monday, at the latest, we’ll have this sorted out.”

I am pushed out of the room to make way for the next patient. They leave the trolley in a corner of the corridor where there is less movement. Someone binds my thigh with a large adhesive bandage, squeezing tightly to form a tourniquet. This is then attached to a parallelepiped-shaped weight, placed over the site of the perforation. I suppose it must have been made of lead, as it weighs much more than something of the kind in stone.

“You’ve got to keep this on for four hours,” they tell me.

I get the message. A vessel with the calibre of the iliac artery has a very strong power of contraction, and when it has been punctured and abandoned, it is capable of leaving us without a drop of blood in just a few minutes.

Nurse Catarina and the fireman, who have been waiting at the door, say goodbye. They are going back to Torres Vedras without me and I am staying here without them. “It’ll be fine, you’ll see,” she assures me in her gentle attentive tone. And then they disappear, off to their own lives. I am left to my own devices, but I am not very good company. I am hungry and dejected, abandoned in a hospital corridor with a lump of lead balancing on my groin and another weighing down my soul. I have had some explosive news and I need to digest it. For tomorrow or Monday I will have an operation on my heart. On my heart! A 90 % obstruction! That’s to say, not one drop of blood can get through the common arterial trunk and half my heart has stopped working. That is why I collapsed. This, after all, explains everything that happened to me.

I don’t know how long I waited there. But the time passed and eventually someone remembered me. I was wheeled along corridors and through doors, and finally we arrived in a two-bed room that was unoccupied. At the bottom, there was a window of smoked glass through which entered very little light, suggesting that outside, it was getting dark. Was that possible? What time was it? Where were all the people?

Some centuries later, João, my wife, arrived with my nephew and niece, who had come down from Oporto to visit me in Torres Vedras. They had peered in through the door of my room in Torres Hospital, but as I wasn’t there, had decided to wait for Nurse Catarina to return. They are trying to put on a brave face, but everyone looks worried and dejected. After a long day of fasting and feeling like I'd been lost in the hospital, my gloomy thoughts break loose, crudely and mournfully.

“They won’t be able to do anything..., no by-pass, they won’t be able to get the mammary artery away from the bone; and it’ll be damaged, all stiff and fibrous from the radiotherapy...”

They try to calm me down. They have spoken to Dr Gil Seabra (João and Ana think he is “lovely”) and he explained everything to them. He showed them coloured images of my heart and said “it was all going to be fine”. They present me with clear positive arguments, arguing that. “...at least we know what the problem is now. It will all get sorted out tomorrow.”

Brilliant! It is from them that I learn that my operation is scheduled for the next day and not Monday, and that after it, I will be like new. Despite everything, I’m a guy with a future, and this is just a plumbing problem! I shut up, though more out of exhaustion than because things were going my way.

They give me dinner and just before lights-out, bring me tea, some biscuits and a Lorenin. I should eat now, because tomorrow I will have to fast again. The countdown has started.

The lights go out and I wait patiently, as if in a queue for morning, for I don’t really believe that sleep is on its way. Curled in the darkness, listening to the sounds emanating from the ward, I take stock, depressingly, of the recent years of my life and of the bad luck that seems to have afflicted me.

I recall things, trying to drag to the first page of consciousness some lines that I read in a medical book, almost two years after completing the last session of radiotherapy:

Cardiac irradiation accelerates coronary disease and more than triples the risk of a fatal myocardial infarction*.

At the time I hadn’t paid much attention. I read it lightly, for it seemed impossible that bad luck would come and bang on my door again, so shortly after I’d got over cancer. Of course I paid even less attention to the detailed description of the effect that radioactive rays could have on the various arteries that irrigate and nourish the heart:

Some studies suggest a high incidence of disease in the common arterial trunk**.

A fistful of tears, black with anguish and bitter as gall, stubbornly mount up beneath my closed eyelids – but they are scanty and evaporate before they can stain that unfamiliar pillow. Blast it!

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Part II

It’ll be nothing serious!

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

11

14th May 1996. There are some dates that remain forever engraved in our memory, as fixed and as permanent as the inscriptions on tombstones. Twenty-to-seven in the morning, a few dozen kilometres south of Cape Carvoeiro. It looks as if it will be a glorious day. Outside, a golden sliver of light is insinuating itself over the horizon, and the blackbirds are challenging each other with cascades of trills and elaborate fugues. I am standing before the bathroom mirror shaving. By 9 o’clock, I will be in Lisbon, where I have two meetings, one in the morning with colleagues and another in the afternoon with a lawyer from the Ministry of Health.

I have just ploughed through the foam on my face and am carefully beginning on my neck. As I move the blade over the left-hand side, I feel a slight burning sensation in the skin. I inspect the site, holding the razor aloft. The burning persists. It is just above a swelling that appeared one or two weeks ago, so small that I hadn’t given it much attention. In fact, I only noticed it because I had to shave over it, and assumed it was just one of those minor ailments that come and go. After all, the body usually takes care of itself, patiently rebuilding its integrity in its mysterious silent way, returning us to our familiar corporal landscape.

But the persistent burning and slight redness of the skin now draws my attention. I pass a finger over the small swelling. Now that I look at it, it seems more prominent than before. Even in the mirror, it looks bigger. My mind runs through all possible causes, anything I can think of that could afflict a chap over 40. And I start spinning up into orbit. Panic had just sunk its teeth into my neck.

For the rest of the day, I found it extremely difficult to concentrate. I tried to relieve the tension by confiding in one of my colleagues during the coffee break, downplaying the situation as much as I could. But that didn’t solve anything. In fact, it only doubled my anxiety.

“I’d get it checked out, if I were you. Do a blood cell count, get a chest X-ray. It’s probably nothing serious, but at least you’ll set your mind at rest.”

“Blood cell count?!” I thought, aghast. Ugh! I’ve always hated needles!

The afternoon dragged out in exasperating detail. I kept my eyes glued to my watch, waiting for the time when I could call Manel, who never got back “before half past eight”, according to Gabriela, his wife.

Manel is my first cousin by blood, but we spent so much time together when we were kids, have so many shared memories, that he is more like a brother to me. What’s more, he’s also a doctor, a specialist in Internal Medicine, and the kind of person that inspires confidence, from a clinical point of view. That was why I thought of him right away, though he lives almost 400 km away in Braga.

He phoned me as soon as he got home and I told him about the swelling. He listened in silence, and asked for more details. Where was it located exactly? What was the consistency? Was it painful? Did it stick to the adjacent tissues? How long had I had it? The usual questions. And I, at the other end of the line, could sense where his reasoning was taking him.

“It might be nothing serious. It could be just a tooth. But it would be better to get it tested, one thing at a time…”

He told me to start taking a light anti-inflammatory, twice a day for four or five days, and then we would see how the swelling reacted. If the ganglion, which is what it seemed to be, did not go down, then it would be a good idea to go to the dentist to have the teeth in the lower jaw checked out.

Although my teeth hadn´t given me trouble for years, I eagerly seized onto this idea. Yes, yes, that was indeed very possible. I’d had bad teeth since a child, terrible teeth! I’m the kind of person that goes three or four times a year to the dentist – in fact, I’ve got a private box reserved for me at the local dental clinic, and my dentist is a very good friend.

A week later, I was in Oporto, reclining in the dentist’s chair with an X-ray of my mandible on display in the light box. The lump had not changed. It was no bigger and no smaller, still firm.

The dentist examined all the teeth that could possibly have been involved in the growth of that ganglion.

“It doesn’t look like it’s come from here,” he said. “Sometimes there can be internal seepage, almost undetectable, generally gram-negative bacteria. It might be that, though I can’t see anything suspicious.”

Then, after further consideration, he added,

“Let me just call a colleague to see what he thinks. He works in plastic surgery – those guys deal a lot with the neck area. They have practice in this kind of thing.”

And he sat down at the telephone. I remained in the chair with the towel around my neck, listening to the conversation unfold.